Plagued by depression and isolation, a man escapes the daily routine and discovers a new dimension in the short film, Program. Director Matthieu Tondeur discusses seeking out film funding, wanting to do more important work, and the challenges of working with 16mm film to shoot his latest project.

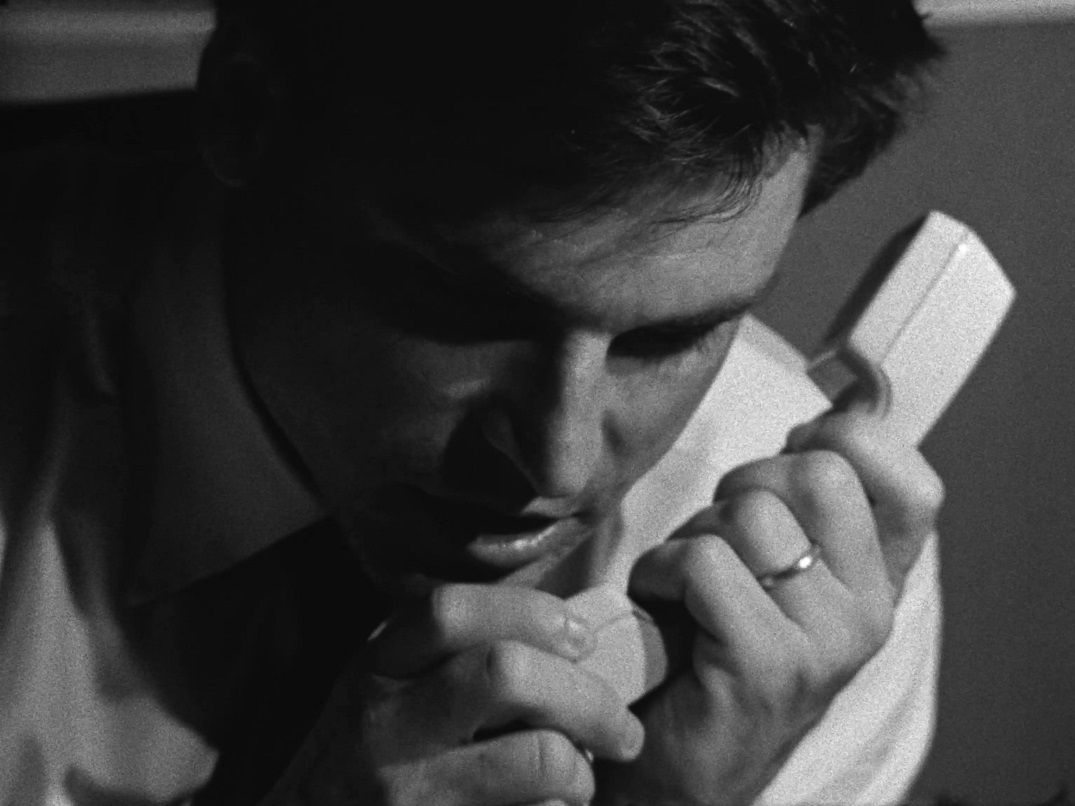

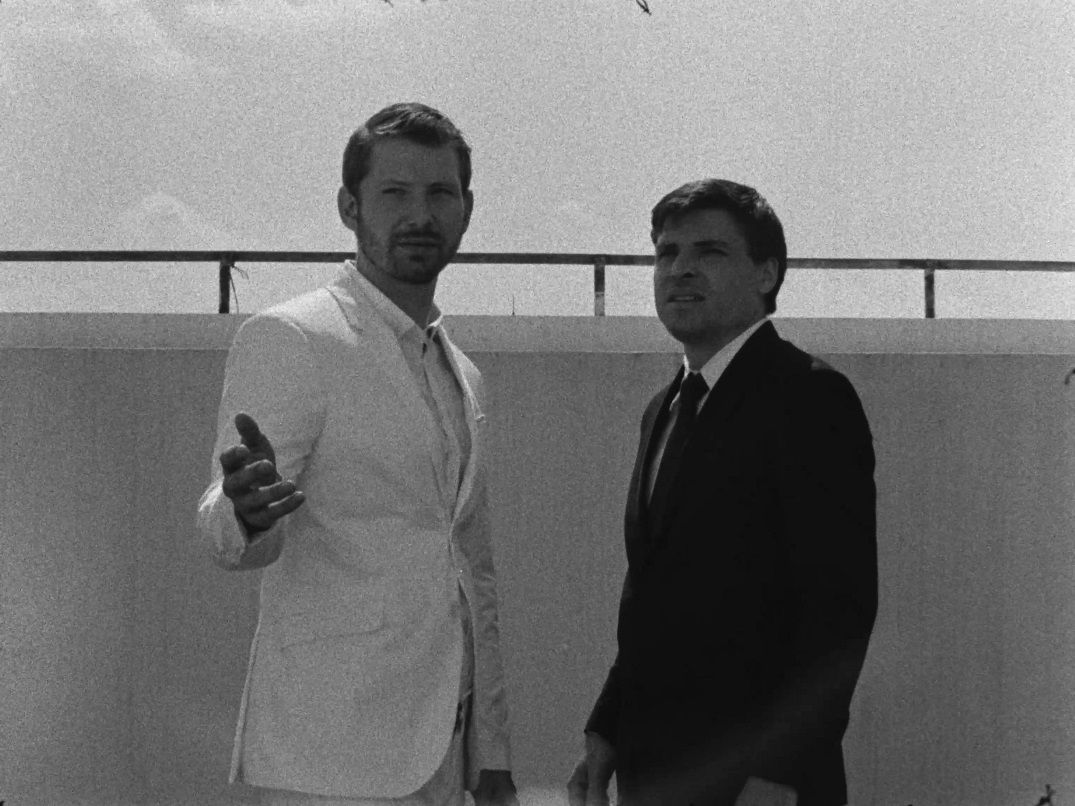

Program follows the tale of a man named Dimitri (played by Siegfried Fau) whose world has been dulled by the routine of everyday life. Following an encounter with a former co-worker (Emil Rehnberg), Dimitri is led to a Mediator (Archibald McColl) who guides him to a place where he obtains both higher wisdom and a better understanding of the self. Along the way, the film explores themes linked to depression, isolation, and symbolic resurrection.

In imaging the idea for the story, director Matthieu Tondeur took inspiration from films such as Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker (1979), Chris Marker’s La Jetée (1962), and the work of French filmmaker Jean Cocteau. And, in order to get the circa-1960s/1970s look he sought to emulate, he shot on 16mm Kodak film he imported to China from the United States. At the same time, Tondeur admits the decision to shoot on film was as much about making a statement about digital imaging and filmmaking as it was about creative aesthetics.

“If you have a scene where the actors don’t move so much, they don’t talk, and you just have a shot of their faces like they’re trying to think of something, with film you still see the film going and you feel time passing,” he observes. “If you shoot something like that with digital it’s clean and it’s like looking at a JPEG image. In film, you don’t move and the time still passes.”

Tondeur’s team employed a number of different cameras—including a Russian Krasnogorsk-3 (K-3) and a vintage Beaulieu camera—to shoot Program. Not only did this limit them to shooting mostly under strong daylight, but the amount of noise the cameras made also meant they had to rely entirely on ADR and foley work for the film’s audio. In addition, they had to say goodbye to tools such as electronic viewfinders and video assist.

“They’re not like professional cameras, so when you look in the viewfinder, it’s not like looking into a viewfinder on an SLR,” he explains. “It’s like a toy and when you look inside it’s dark, the plate is dirty and you can’t clean it—so it’s very hard to focus.”

"Usually you have four-hundred feet of film per reel, but ours was just one-hundred feet—just two minutes of film—and I couldn’t trust the counter on the camera because it was so old."

Principle photography took place between July and September 2017—a period when Shanghai experienced some of its hottest days ever on record. And, working under those conditions required a huge amount of patience, especially when Tondeur’s team were losing thirty-to-forty minutes at a time just to change over rolls in the camera.

“Usually you have four-hundred feet of film per reel, but ours was just one-hundred feet—just two minutes of film—and I couldn’t trust the counter on the camera because it was so old,” he says. “Every time I’d start shooting the AD or the line producer would click the timer on their phones, but even that I couldn’t trust because I didn’t know how much film I’d used to load it into the camera.”

Despite the numerous and time-consuming complications which came with shooting on film, Tondeur says he nevertheless decided to largely shun the use of storyboards or any extensive pre-planning of shots for the project.

“In the past, I used to pre-plan shots, but I was very unhappy with the results because I thought it was too formal and too boring,” he says. “I’d have my shot list and I’d work as fast as I could because I knew I had to get all these shots and then I’d realize that I hadn’t thought to do all of this other stuff I wanted to do because I was so much into my list.”

"When you begin to scan the roll and you see one or two frames and when you begin to see the result it’s like Christmas—I was so fucking happy."

When it was all done, Tondeur ended up with almost two dozen rolls of exposed film at a shooting ratio of roughly five-to-one compared with the film’s ten-minute run-time. And, after initially working first from his kitchen, he finally got some help from a small independent lab in Shanghai to develop the film.

After processing the footage, Tondeur constructed a homemade scanner and through trial-and-error converted each roll of film into a series of digital images which he then reassembled at 24-frames-per-second so he could start editing. The entire process took four-to-five hours per reel and in some cases he had to wait upwards of two-to-three weeks after shooting before he could see the final results.

“The nice thing about film was that I knew it was just a matter of time because I knew even if I had to scan it frame-by-frame I’d do it and I knew nobody was going to do it except me,” he says. “When you begin to scan the roll and you see one or two frames and when you begin to see the result it’s like Christmas—I was so fucking happy.”

ALL Club in Shanghai is set to host the Program release party this upcoming Thursday, November 23 and, as Tondeur states, he is already turning his focus to the challenge of raising the funding for a feature-length version of the film.

“The most important thing for me is to find the financing to do bigger projects,” he says. “This is my only interest—not to have all the stuff on the posters or to be famous or something like that.”

Ultimately, Tondeur says that the difficulties he endured in making Program taught him some important lessons and gave him an even greater appreciation for the value of the work filmmakers and other artists do.

“Even though I’m still young, I want to switch my films to be more important,” he concludes. “I don’t want to do ten bullshit movies and then when I’m sixty do something serious. So, with this film I learned that I want to do something that’s relevant and right now.”