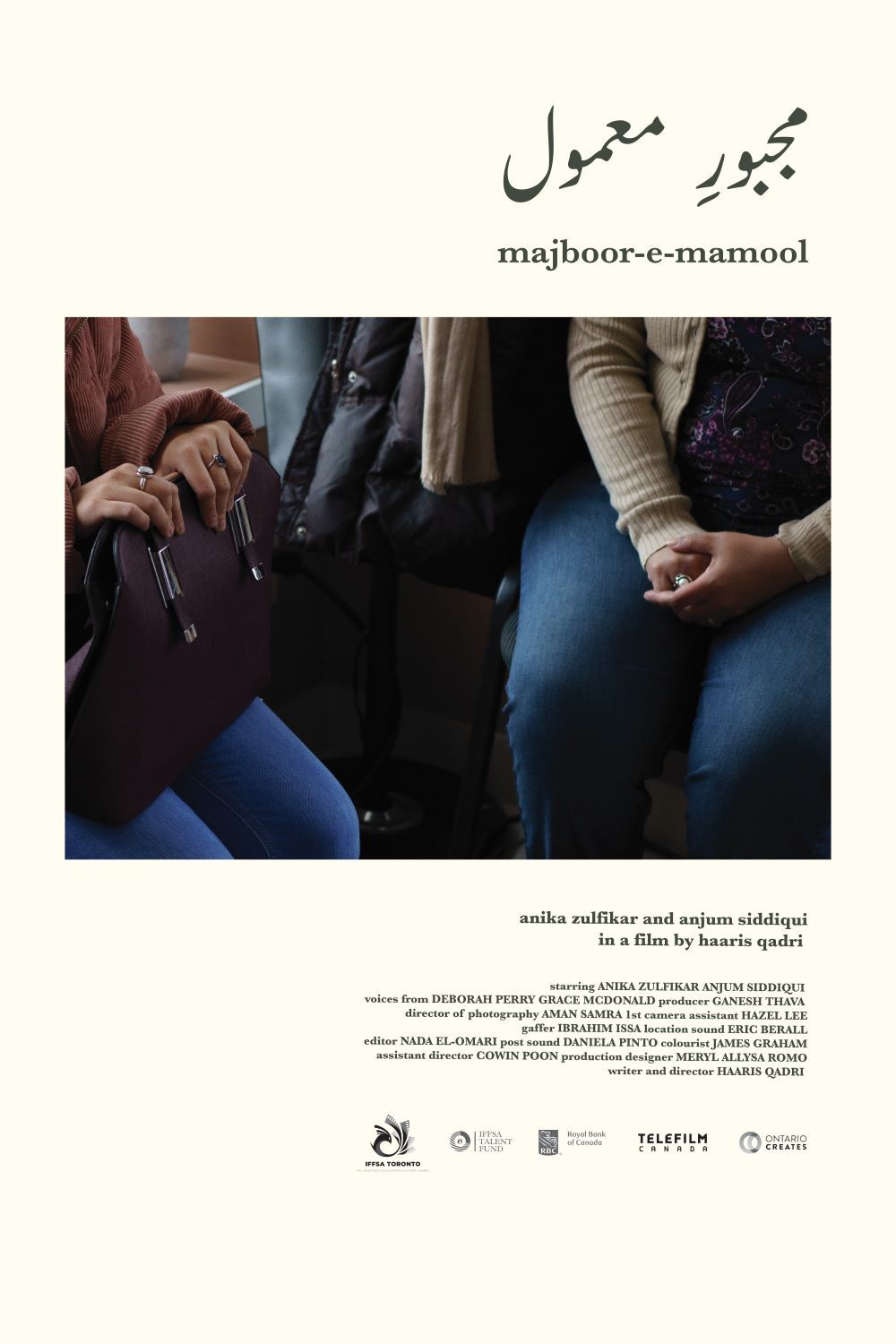

A first-generation Canadian daughter and her immigrant mother struggle to get through a trip to the doctor in Majboor-e-Mamool. We chat with writer-director Haaris Qadri about the challenges of adapting to life in diaspora and the making of his new family drama.

Majboor-e-Mamool tells the story of a first-generation Canadian daughter (played by Anika Zulfikar) who takes her mother (Anjum Siddiqui) to a doctor’s appointment, where she must act as both caretaker and translator.

The bilingual Urdu and English-language film offers a stark portrayal of the relationship between immigrant parents and their children and the feelings of frustration that can accompany familial obligations.

Born in New York and raised in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) by Pakistani parents, writer-director Haaris Qadri says he was motivated to tell the story by his own diasporic heritage and a fascination with intergenerational differences.

“The film is about how, as immigrant kids, we sometimes have to be parents to our parents, and the feeling of guilt when we’re tired of doing it,” Qadri says. “We love our parents and we want to take care of them, but everyone has their off days, thinking, ‘Why can’t you just do this yourself?’ It’s about grappling with those feelings while actually on one of those trips.”

The story was also inspired by the relationship between Qadri’s sister and his mother and numerous family trips to the doctors, as well as some of the personal burnout he experienced in the early days of the COVID pandemic. As a result, he admits that at times he worried that the project would hit a bit too close to home.

“I started writing it and then I freaked out and thought, ‘Wait, should I be writing this? Is this alright?’ I talked to my sister about it because it was her story at the end of the day,” he says. “She was kind of, ‘Yeah, if you feel you want to write about it, go for it.’ So, I wrote it and I had a rough script, but then I sat on it for a year and didn’t really touch it.”

“I wanted to make sure there was empathy for both characters and that I didn’t reduce them to the stereotype of the nagging mom or the bratty kid that you just hate.”

Although he allowed himself space to take creative liberties, he adds that penning the story was very much an exercise in “writing what you know” and that there were times when the story felt like it was writing itself.

“In the first draft, the dialogue was very easy to write. It was very much like, ‘OK, I know how this is going to go. It’s a trip to the doctor.’ Structurally, it was already there for me,” Qadri says. “But, I wanted to make sure there was empathy for both characters and that I didn’t reduce them to the stereotype of the nagging mom or the bratty kid that you just hate.”

The entire eight-and-a-half-minute film is shot in just four long takes (each with the camera set in a static position). As Qadri explains, the simplicity of the approach was something the production team discovered along the way.

“We did rehearsals on location, but we weren’t happy with the way it looked. Then, on the day of production, our DP Aman Samra found a different spot to set the camera and asked if the actors could just do the whole scene,” he recalls. “We ran through the scene and that’s where we were like, ‘OK, now we have a visual language where we’re able to play out these scenes within the frame – maybe we should keep this up.’”

“It has empowered me to write stuff that doesn’t need to have a lot of high-stakes drama.”

He adds that the style fit well with the tone and the scale of the work. Moreover, he says that the final result gave him more confidence as a filmmaker to deliver a pared down narrative (while still conveying the desired emotions).

“If I’d decided to have more scenes, I don’t think the movie would have been as good. Now, as a writer-director, I also feel more comfortable with a story that doesn’t have all of this conflict,” Qadri says. “It has empowered me to write stuff that doesn’t need to have a lot of high-stakes drama. I want to keep exploring making films with this kind of feeling.”

Majboor-e-Mamool has screened at a number of festivals and events in the Toronto area and Qadri says he is currently exploring options for wider distribution. He adds that he has been surprised by the universality and the ability of audiences to relate to the story.

“I think we forget that other people have experienced things like this, too. At our first screening someone with a completely different background came to me and said, ‘I can relate to this because it reminds me of taking my grandmother to see the doctor,’” Qadri says. “I was like, ‘Oh, right, there are different layers to this.’ Sometimes it’s not language, sometimes other things, but I think many people have experienced this at one point in their life.”

Connect with Haaris Qadri via his website here or on Instagram here (@haarisqadri).